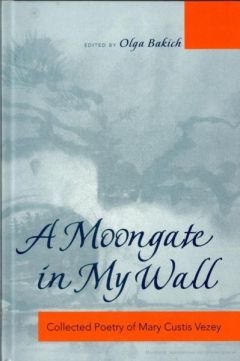

Мария Визи - A moongate in my wall: собрание стихотворений

[1967]

540. «Somewhere…»

Somewhere

there is a gate that I must find and open,

take out the bolt and lilt the latch and push,

and then the road ahead will stretch away

smooth, clear and safe for me to walk at leisure;

a small white gate, wrought in a low white fence,

along the outskirts of this great dense wood.

There must be somewhere

in the tall brush and thicket on my trail

a mark, a sign, perhaps a broken twig,

a tree peculiarly bent, a stone

lying against another;

there must be somewhere

an indication, maybe even arrow

pointing that way, so that I may follow;

it cannot be that I have not remembered

those previous markings,

and have lost the trail.

[1960s]

541. «High in the air, the high blue air above us…»[242]

High in the air, the high blue air above us,

where birds and men fly peacefully together,

for endless centuries, the long lost notes

of many songs have floated by, unheard

to living ears.

We have not yet

become quite strong enough to catch those songs

and hear and tame them for the world to know,

but they are there, for they were never lost

completely. And if sometimes, in the haze

along the fringes of this life

we think we meet

a sudden melody that we have never known,

barely distinguished words, perhaps a rhyme

that we reach out to touch —

we vainly strain, but all that we can feel

is some vague sense of beauty

created somewhere once, and waiting for us,

not quite completely lost,

nor yet recaptured.

[1960s]

542. «Can it be true, in hours of grief and anger…»

Can it be true, in hours of grief and anger

that all one's past will disappear afar

just like the soft sound of some forgotten music,

like in the dark of night a fallen star?

[1980s]

543–561 My China[243]

543. «I put my brushes carefully, one by one…»

Arranging the brushes, and picking the right

one to write a poem.

I put my brushes carefully, one by one,

into their respective cones

in the brass brush stand,

meticulously smoothing each sensitive tuft with my fingers,

to make a pinpoint end.

I pull out the small white bone latch

of my ink box,

lifting its black and gold silk lid.

The ink tablet, half covered with carved inscription,

lies before me.

I pull out the two white bone pieces

latching the powder-blue silk covers

of a small thick volume.

The ivory-white rice paper page

is blank.

The moon has set over the western horizon

and night fragrance is drifting into my window.

I pick a brush of the needed thickness,

touch the surface of water in a porcelain cup

and caressing the ink tablet gently,

write down a poem.

544. «Two ladies stand on an open marble surface…»

A favorite scroll on the east wall of my room.

Two ladies stand on an open marble surface,

and the mist of the April morning

swirls at their silken feet;

the verdure of the white-barked pines,

almost black against the still white sky,

clouds over the bright blue tiles

of the small pavilion.

Far in the distance, all sense of perspective lost

in the subtleties of the mist,

hang the curling cliffs of the mountains,

without top or bottom,

wrapped in the twisting and winding scarves

of the April mist.

545. «In early spring, bright blossom liven…»

In early spring, bright blossom liven

the clay walls of Tung-Chow-fu.

Around the ancient town of Tung-Chow-fu

a great grey wall of brick and earth was built

some centuries ago. A deep, wide moat

was dug and filled with water.

None but friends

could enter through the barred and guarded gate.

Now peace hangs sweetly over Tung-Chow-fu.

The wall has crumbled down in many spots,

and only kingfishers disturb the sleep

of aged willow trees that, drooping, touch

the lazy curling wavelets of the moat.

All there is green and quiet.

In the spring

it is a joy to cross the stepping stones

and climb the wall, and see the almonds bloom

scarlet against the background of the grey.

546. «At Wu-Chih-Mi the little local train…»

Listening to the evening stillness

at Wu-Chih-Mi.

At Wu-Chih-Mi the little local train

stops.

I step off and breathe the summer warmth.

At Wu-Chih-Mi there aren't many dwellings.

It dozes lying in its quiet valley

in summer twilight as the hills around it

turn rose and violet and transparent blue

before the night.

I walk across the green and soundless meadow

and soon I see the lanterns of the sky

reveal their silken brilliance one by one.

Alone I stand and listen to the stillness

at Wu-Chih-Mi

and watch the silver dipper

above the northern hilltops as it tips

to quench the thirsting of my day-parched soul

with the beatitude of simple peace.

547. «Around the bend of the Yalu…»[244]

A field of wild iris, that few people know about.

Around the bend of the Yalu

where the cliffs come close to the sparkling, chattering water,

suddenly you come to an open meadow

all purple with wild iris.

This meadow is like a green jade bowl

held by cliffs on three sides

with a grove of birches framing the river bank on the fourth.

Tie your horse to a birch trunk; let him nibble

on the sweet wild strawberries at his feet. Look:

What peace, what silence!

No one here to pluck these myriad blooms of deep purple,

more plentiful than the grass,

evidently so carefully tended

by a kind gardener.

548. «We sailed in a small river boat…»

A grey town, full of people very busy living.

We sailed in a small river boat

up the wide canal on the way to Zo-Ssu

one April day.

We passed through a town

and sailed under its bridge,

a high curved stone bridge,

linking two halves of the town.

The bridge was grey, like the walls

of the houses on either side,

but a very busy life

was evident everywhere,

people selling their wares and walking about the streets,

meeting above on the bridge to enjoy the sun and to engage in

conversation,

women washing their clothes at the edge of the stream below,

and several naked children, happy to be near water,

jumping in for a swim from the sampans anchored ashore.

549. «Ching-pu is an elderly man and all his chores are completed…»

Watching the river boats, having nothing else to do.

Ching-pu is an elderly man and all his chores are completed,

the tilling of fields, the raising of crops and of sons.

Ching-pu sits back on his heels on the sunny terraced knoll

smoking his long-stemmed pipe filled with bitter tobacco,

holding his slender pipe with withered yellow hand,

watching the river below hurrying round the bend,

watching the river sampans swiftly propelling themselves,

prow to the muddy current,

around the bend of the river,

towards the city beyond.

550. «Your gate is heavy, strong, and always barred…»[245]

Some are closed, and some are open;

I like the latter.

Your gate is heavy, strong, and always barred.

Its face is bright vermilion touched with brass.

A stout kai-meng-de guards it day and night

and just a chosen few may step inside.

But I prefer a moongate in my wail —

an open gate that has no use for locks.

Come, let us walk right through and see the pines

shedding dark needles on the moonlit steps!

551. «The white sands on the sloping shore of the river…»

He was almost as old as the river,

and he made more noise than the river itself

The white sands on the sloping shore of the river

lie silent, except for the lapping,

continuous lapping

of the yellow water

against the edge of the slope,

— the great mass of water

poured powerfully

down the deep trough of its old bed.

liven the water grasses,

crashing close to the current,

hold the wav'es of their surface

silently toward the sun.

Suddenly, a heavy splash disturbs the silence,

as the aged bulk of a huge river tortoise

turns swiftly

near the top of the yellow water,

to snatch a minnow.

552. «It was a lazy summer noon, as I sat in the stern of a flat-bottomed boat…»[246]

The blue parasol may have been becoming.

I do not know; I hope it was.

It was a lazy summer noon, as I sat in the stern of a flat-bottomed boat,

holding a blue parasol over my head and back.

My boatman rowed unhurriedly through the rushes,

the tall rushes crowding a narrow stream

across the Sung-Hwa-kiang.

I sat enjoying the blue of the sky,

the gold of the sun, the green of the grass and the ripples,

and I did not know whether I was pretty or not,

in my light summer gown,

against my light blue parasol —

I did not know whether I wras pretty or not,

I had not expected to meet you rowing towards me,

swiftly slicing the rushes with the sharp prow of your boat,

as you returned from your early morning fishing.

553. «He was a shepherd and he spent his hours…»[247]

A person encountered in the Western I lills near

Beitsing

He was a shepherd and he spent his hours

upon a hillside taking care of sheep.

He slept in his small hut of mud and straw

and ate his rice and sometimes drank his tea.

His hands were gnarled and grimy and his clothes

he hardly ever changed from month to month

for he was one of the unwashed who lived

so many li from rivers or a spring.

In early morning, when some stranger chanced,

dangling his dusty legs, on donkey back

to pass his hut, the friendly shepherd called

by way of greeting, —

«Have you had your rice?»

554. «At daybreak, as the skies lighten…»