Clive Cussler - Spartan Gold

The water taxi pulled to a stop and Sam and Remi climbed out. Together they stared at the surrounding buildings.

“No matter how many times I see it, it always takes my breath away,” Remi said.

Known to English tourists as Saint Mark’s Plaza, the Piazza San Marco is in fact a trapezoid sitting at the eastern mouth of the Grand Canal. Famous for its pigeons and geometric “hopscotch” stone inlays, it is perhaps the most famous plaza in all of Europe, home to some of Venice’s greatest attractions, many dating back a thousand years or more.

Sam and Remi turned in a circle, taking it in as if seeing it for the first time: Saint Mark’s Basilica, with its Byzantine domes and spires; the Campanile, its three-hundred-foot bell tower; the imposing Gothic Palazzo Ducale, or Doge’s Palace; and finally, directly opposite the basilica, the Ala Napoleonica, the one-time home of Napoleon’s administrative residence.

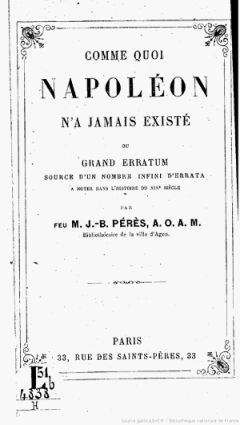

Whether a coincidence or not they would soon know, but they were keenly aware of Napoleon’s connection to Venice and the Piazza San Marco, which he’d dubbed “the drawing room of Europe.” In 1805, soon after Venice was named part of the newly created Kingdom of Italy, Napoleon ordered the Ala Napoleonica built after realizing his initial choices—the Zecca, or mint; the Libreria Marciana; and the Procuratie Nuove—were not large enough to accommodate his court.

It was nearly six o’clock and the sun was dipping toward the horizon over the roof of the Marciana Library. Some of the piazza lights had come on, casting amber pools on the arches and domes. Most of the day’s tourists had left and the piazza was quiet save for the background babble of voices and the cooing of the pigeons.

“Who are we meeting?” Remi asked.

“The curator,” Sam replied. “Maria Favaretto.”

Before catching their two o’clock Lufthansa flight from Salzburg, Sam had called the curator of their destination, the Museo Archeologico, and introduced himself. Luckily, Signora Favaretto had heard of them. Their discovery of the lost diary of Lucrezia Borgia, the fifteenth-century Machiavellian political operator/seductress, a year earlier in Bisceglie had been front-page news in Venice, she told Sam. In fact, a former colleague of hers was the assistant curator of the Vatican Library’s Museo Borgiano, where he and Remi had donated the diary. Favaretto agreed to meet them for an after-hours visit of the Museo Archeologico.

“Is that her?” Remi asked, pointing.

A woman was waving to them from inside one of the entrance arches to the Procuratie Nuove, in which the Museo Archeologico was partially housed; the rest was located within the Biblioteca Nazi onale Marciana—the National Library of St. Mark’s. Sam and Remi walked over to the woman.

“Signor Fargo, Signora Fargo, I am Maria Favaretto. It’s my pleasure to meet you.”

“Please call us Sam and Remi,” Remi said, shaking her hand.

“And I’m Maria.”

“Thank you for your help. We hope we aren’t inconveniencing you.”

“Not at all. Remind me again, what period are you interested in?”

“We’re not positive, but none of the references we found are later than the eighteenth century.”

“Good. I think we’re in luck. If you’ll follow me, please.”

She led them through the arch, across a breezeway done in terra-cotta and cream tiles, and into the museum. They followed her past displays of Egyptian sarcophagi and Assyrian chariots, Etruscan statues and vases and Roman busts, Byzantine ivory carvings and Minoan earthenware jars.

Maria stopped at a wooden door and unlocked it with a key. They went down a long, dimly lit hallway. She stopped. “This is our not-for-public library. Given what you were asking about I thought the best person to help you would be Giuseppe. He doesn’t have a title per se, but he’s been here longer than anyone—almost sixty years. He knows more about Venice than anyone I know.” She hesitated, cleared her throat. “Giuseppe is eighty-two and a little . . . odd. Eccentric is the word, I think. Don’t let that worry you. Just ask your questions and he’ll find the answers.”

“Okay,” Sam said with a smile.

“The reason I asked about your time frame is that Giuseppe is what you might call a throwback. He has no interest in anything modern. If it didn’t happen in the nineteenth century or earlier, it doesn’t exist for him.”

“We’ll keep that in mind,” replied Remi.

Maria opened the door and gestured for them to step through. “Just press the buzzer on the wall here when you’re done. I’ll come back for you. Good luck.” She shut the door.

The museum’s library was long and narrow, measuring two hundred feet by forty feet. The walls were not walls at all, but floor-to-ceiling bookcases. They were twenty feet tall. On each of the four walls was a rolling wooden ladder. A single, ten-foot-long worktable and a lone hard-backed chair sat in the center aisle. Halogen pendants hung from the ceiling, casting soft pools of light on the green-tiled floor.

“Is someone there?” a voice called.

“Yes,” Sam replied. “Signora Favaretto let us in.”

As their eyes adjusted they could see a figure standing atop the ladder at the far end of the library. He was perched on the top rung, finger tracing along the book spines, occasionally nudging one inward or sliding one outward. After a moment the man climbed down and started shuffling down the aisle toward them. Thirty seconds later he came to a stop before them.

“Yes?” he said simply.

Giuseppe was barely five feet tall with wispy white hair that jutted out from his head at all angles. He couldn’t have weighed more than ninety pounds. He stared up at them with surprisingly sharp blue eyes.

“Hello. I’m Sam and this is—”

Giuseppe waved his hand dismissively. “You have a question for me?”

“Um, yes. . . . We’ve got a riddle on our hands. We’re looking for the name of a man, probably from Istria in Croatia, that might have a connection to either Poveglia or Santa Maria di Nazareth.”

“Give me the riddle,” Giuseppe ordered.

“ ‘Man of Histria, thirteen by tradition,’ ” Sam recited.

Giuseppe said nothing, but stared at them for ten seconds as he pursed his lips from side to side.

Remi said, “We also think he might have something to do with lazarets—”

Abruptly Giuseppe turned around and shuffled away. He stopped in the aisle, then stared at each wall in turn. His index finger tapped the air before him in the manner of a slow-motion conductor.

“He’s cataloging books in his head,” Remi whispered.

“Quiet, please,” Giuseppe barked.

After two minutes Giuseppe went to the right-hand wall and pushed the ladder to the far end. He climbed up, plucked a book off the shelf, paged through it, then put it back and climbed back down.

Five more times he repeated the process, staring at the walls, conducting the air, and mounting the ladder before climbing back down and shuffling back to them.

“The man you’re looking for is named Pietro Tradonico, the Doge of Venice from 836 to 864. Chronologically he was the eleventh Doge, but by tradition he is considered the thirteenth. Tradonico’s followers fled to the island of Poveglia after he was assassinated. They had some huts near the island’s northeastern corner.”

With that, Giuseppe turned and started shuffling away.

“One more question,” Sam called.

Giuseppe turned, said nothing.

“Is Tradonico buried there?” asked Sam.

“Some think so, some not. His followers claimed the body after his assassination, but no one knows where it was taken.”

Giuseppe turned again and doddered away.

Remi called, “Thank you.”

Giuseppe didn’t reply.

“Did you find what you were looking for?” Maria asked a few minutes later when they came out. After they’d pushed the buzzer beside the door it had taken her five minutes to arrive. During that time, Giuseppe continued about his work as though they didn’t exist.

“We did,” Sam replied. “Giuseppe was everything you said he’d be. We appreciate your help.”

“It’s my pleasure. Is there anything else I can do for you?”

“Since you’re being so helpful . . . what’s the best way to get to Poveglia?”

Maria stopped walking and turned to them. Her face was drawn. “Why would you want to go to Poveglia?”

“Research.”

“You’re welcome to use our facilities. I’m sure Giuseppe would—”

Sam said, “Thank you, but we’d like to see it for ourselves.”

“Please reconsider.”

“Why?” Remi asked.

“How much do you know about Poveglia’s history?”

“If you’re talking about the plague pits, we read—”

“Not just those. There’s much more. Let’s have a drink. I’ll tell you the rest.”

CHAPTER 54

Explain it to me again,” Remi whispered. “Why couldn’t this wait till morning?”

“It is morning,” Sam replied, turning the wheel slightly to keep the bow on course. Though their destination showed no lights, its bell tower was nicely silhouetted against the night sky.

From above, Poveglia looked like a fan, measuring five hundred yards from its flared tip to its base, and three hundred yards at its waist where a narrow, walled canal bisected the island from west to east, save for a sandbar in the center.

“Don’t get technical on me, Fargo. As far as I’m concerned, two A.M. is the middle of the night. It isn’t morning until the sun comes up.”

After drinks with Maria they’d managed to find an open boat rental office. The owner had only one craft left, a twelve-foot open dory with an outboard motor. Though not luxurious by any means, it would suffice, Sam decided. Poveglia was only three miles from Venice, inside the sheltering arms of the lagoon, and there was little wind.

“Don’t tell me you bought into Maria’s stories,” Sam said.

“No, but they weren’t exactly cheery.”

“That’s the truth.”

In addition to having served as a dumping ground for plague victims, throughout its thousand-year history Poveglia had been home to monasteries, colonies, a fort and ammunition depot for Napoleon, and most recently in the 1920s, a psychiatric hospital.

In frightening detail Maria had explained that the doctor in charge, after hearing the patients complain about seeing the ghosts of plague victims, began to conduct crude lobotomies and gruesome experiments on the inmates, his own brand of medical exorcism.

Legend had it that the doctor eventually began seeing the same ghosts his patients had reported and went insane. One night he climbed up the bell tower and jumped to his death. The remaining patients returned the doctor’s body to the bell tower and sealed the exits, entombing him forever. Shortly thereafter the hospital and the island were abandoned, but to this day Venetians reported hearing Poveglia’s bell ringing or seeing ghostly lights moving in the windows of the hospital wing.

Poveglia was, Maria told them, the most haunted place in Italy.

“No, I don’t buy the part about the ghosts,” Remi said, “but what went on in that hospital is well documented. Besides, the island’s closed to tourism. We’re breaking and entering.”

“That’s never stopped us before.”

“Just trying to be the voice of reason.”

“Well, I have to admit it’s very creepy, but we’re so close to solving this riddle I want to get it done.”

“Me, too. But promise me something: One gong from that bell tower and we’re gone.”

“If that happens you’ll have to race me to the boat.”

A few minutes later the mouth of the canal came into view. A few hundred yards down the shoreline they could see the dark outline of the hospital wing and bell tower rising over the treetops.

“See any phantom lights?” Sam asked.

“Keep joking, funny man.”

He maneuvered the dory through the chop created by the lapping waves and they slipped into the canal. Sheltered from the seaward side, the canal saw little circulation; the surface was brackish and dotted with lily pads and in some places the water was only a few feet deep. To their right a brick wall draped in vines slipped past; to their left, trees and scrub brush. Above they heard the rasp of wings and looked up to see bats wheeling and diving after insects.

“Just great,” Remi muttered. “It had to be bats.”

Sam chuckled. Remi had no fear of spiders or snakes or bugs, but she loathed bats, calling them “rats with wings and tiny human hands.”

Ten minutes later they reached the sandbar. Sam revved the engine, driving the bow onto the soil, then Remi got out and dragged the dory a few feet higher. Sam joined her and staked down the bow line. They clicked on their flashlights.

“Which way?” she asked.

He pointed to their left. “North end of the island.”

They walked across the sandbar, then up the opposite bank to a dense hedge of scrub. They found a thin spot, pushed their way through, and emerged in a football-sized field surrounded by low trees.

Remi whispered, “Is this . . . ?”

“It might be.” None of the maps of Poveglia had agreed upon the exact locations of the plague pits. “Either way, it’s odd that nothing’s growing here.”

They continued across the field, stepping gingerly and shining their flashlights over the dirt. If this was the site of a plague pit, they were treading on the remains of tens of thousands of people.

When they reached the opposite tree line Sam led them east for a hundred feet before turning north again. The trees thinned out and they emerged into a small clearing filled with knee-high grass. Through the trees on the other side of the clearing they could see moonlight glinting off water. In the distance rang a gong.

“Buoy in the lagoon,” Sam whispered.

“Thank God. My heart skipped a couple beats.”

“Here’s something.” They walked forward and stopped before a block of stone peeking above the grass. “Must have been part of a foundation.”

“Over there, Sam.” Remi was shining her flashlight at what looked like a fence post on the right side of the clearing. They walked over. Affixed to the post was a Plexiglas-enclosed placard:

Ninth-century site of the followers of Pietro Tradonico, Doge of

Venice 836 to 864. Remains disinterred and relocated in 1805.

—Poveglia Historical Society

“If Tradonico was here, he’s gone now,” Remi said.

“ ‘Relocated in 1805,’ ” Sam read again. “That was about the time Napoleon was crowned king of Italy, right?”

Remi caught on: “And about the time he had Poveglia converted to a munitions depot. If Laurent was with him, this is probably where they got their inspiration for the riddle.”