Clive Cussler - Spartan Gold

“I agree. Let’s move on. Try the ‘King of Iovis.’ When did he die?”

Sam checked. “No such person. Iovis wasn’t a kingdom or a territory. Here’s something. . . . We’re grouping the words wrong—‘Iovis Dies.’ The original Latin for Thursday.”

“King of Thursday?”

“Jupiter,” Sam said. “In Roman mythology, Jupiter is the king of gods, like Zeus is to the Greeks.”

Remi caught on: “Also known as the Jovian planet. So from the Latin Iovis they got Jovis, then Jovian.”

“You got it.”

“So try a search with ‘Jupiter,’ ‘dubr,’ ‘three,’ and ‘seven.’ ”

“Nothing.” He added and subtracted the search terms and again came up empty. “What’s the fifth line?”

“ ‘Temple at the Conqueror’s Crossroads.’ ”

Sam tried “Jupiter” combined with “Conqueror’s Crossroads,” turned up nothing, then tried “Jupiter” and “temple.” “Bingo,” he muttered. “There are lots of temples dedicated to Jupiter: Lebanon, Pompeii . . . and Rome. This is it. In Rome the Capitoline Hill is dedicated to the Capitoline Triad—Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. And here’s the kicker: it’s located on one of the Seven Hills of Rome.”

“Let me guess: the third one. ‘The third of seven shall rise.’ ”

“Yes.” Sam found an artist-rendered map of how the area would have looked during Rome’s peak. He turned the screen so Remi could see. After a few moments she smiled. “You see anything that looks familiar there?”

“You mean other than Capitoline Hill? No.”

“Look due west.”

Sam traced his finger across the screen and stopped on a blue serpentine line running from north to south. “The Tiber River.”

“And what’s the Celtic word for water?”

Sam grinned. “Dubr.”

“If those were the only lines to the riddle I’d say we’d need to go to Rome, but something tells me it isn’t going to be that easy.”

Having assumed the last line—Pace east to the bowl and find the sign—would sort itself out whenever they reached their destination, they turned their focus to the fourth and fifth lines—Alpha to Omega, Savoy to Novara, Savior of Styrie / Temple at the Conqueror’s Crossroads—and spent the next two hours filling their notepads and going in circles.

A little before midnight Sam leaned back in his chair and raked his hands through his hair. He stopped suddenly. Remi asked, “What is it?”

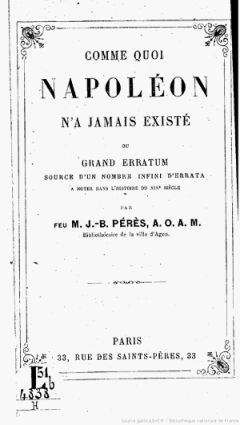

“I need the biographical sketch of Napoleon—the one Selma e-mailed us.” He looked around, grabbed his iPhone from the nightstand, and called up the correct e-mail. “There,” he said. “Styrie.”

“What about it?” She paged through her notes. “It’s a region in Austria.”

“It was also the name of Napoleon’s horse—or at least until the Battle of Marengo in 1800. He renamed Styrie to commemorate the victory.”

“So the ‘Savior of Styrie’ . . . someone who saved Napoleon’s horse. Are we looking for a veterinarian? Doctor Dolittle, perhaps?”

Sam chuckled. “Probably not.”

“Well, it’s a start. Let’s assume the two previous phrases—‘Alpha to Omega, Savoy to Novara’—have something to do with whoever did the saving. We know Savoy is a region in France and Novara is a province in Italy—”

“But they’ve also got a Napoleon connection,” Sam replied. “Novara was the headquarters for his Department of the Kingdom of Italy before it was given to the House of Savoy in 1814.”

“Right. Go back to the previous phrase: ‘Alpha to Omega.’ ”

“Beginning and end; birth and death; first and last.”

“Maybe it’s talking about whoever ran the Department of the Kingdom of Italy first, then took over in 1814. No, that’s not right. We’re probably looking for a single name. Maybe someone who was born in Savoy and died in Novara?”

Sam punched different terms into Google, playing with combinations. After ten minutes of this he came across an encyclical on the Vatican website. “Bernard of Menthon, born in Savoy in 923, died in Novara in 1008. He was sainted by Pope Pius XI in 1923.”

“Bernard,” Remi repeated. “As in Saint Bernard?”

“Yes.”

“I know this isn’t it, but the only thing that comes to mind are the dogs.”

Sam smiled. “You’re close. The dogs gained their notoriety from the hospice and monastery at the Grand St. Bernard Pass. We were there, Remi.”

Three years earlier they’d stopped at the hospice during a biking trip through the Grand St. Bernard Pass in the Pennine Alps. The hospice, while best known for ministering to the injured and lost since the eleventh century, had another claim to fame: in 1800 it had offered respite to Napoleon Bonaparte and his Reserve Army on their way through the mountains toward Italy.

“I don’t know if there are any accounts of it,” Sam said, “but it doesn’t take much of a leap to imagine a grateful Napoleon handing Styrie over to the hospice’s farriers. In the middle of a blizzard it would have seemed like salvation.”

“It would at that,” Remi replied. “One last line: ‘Temple at the Conqueror’s Crossroads.’ Those mountains have seen their share of conquerers: Hannibal . . . Charlemagne . . . Roman legions.”

Sam was back at the laptop typing. His query—“Jupiter,” “temple,” and “Grand St. Bernard”—returned an Oxford University article recounting an expedition to the site of the Temple of Jupiter at the summit of the pass.

“The temple dates back to A.D. 70,” Sam said. “Constructed by Emperor Augustus.” He called up the location on Google Earth. Remi leaned over his shoulder. They could see nothing but jagged gray granite.

“I don’t see anything,” Remi said.

“It’s there,” Sam said. “It may be just a pile of stones, but it’s there.”

“So if we look east of the temple . . .” Using her index finger she traced a line across the lake to the cliff along the southern shoreline. “I don’t see anything that looks like a bowl.”

“Not enough resolution. We’ll probably have to be standing right on top of it.”

“That’s great news,” Selma said when Sam and Remi called ten minutes later. She leaned back in her chair and took a sip of tea. Without her afternoon cup of Celestial Seasonings Red Zinger her afternoons tended to drag. “Let me do a little research and I’ll get back to you with an itinerary. I’ll try to get you on the first flight out in the morning.”

“The sooner the better,” Remi said. “We’re in the home stretch.”

“So if we’re to believe Bucklin’s story about the Immortals and the Spartans, then we’re assuming the Spartans took the Karyatids through Italy into the Grand St. Bernard, then . . . what?”

“Then twenty-five hundred years later Napoleon somehow stumbles onto them. How or where we won’t know until we make the walk from the temple.”

“Exciting stuff. It almost makes me wish I were there.”

“And leave the comfort of your workroom?” Remi said. “We’re shocked.”

“You’re right. I’ll look at the pictures when you get home.”

They chatted for a few more minutes then hung up. Selma heard the scuff of a shoe and turned around to see one of the bodyguards Rube Haywood had sent moving toward the door.

“Ben, isn’t it?” Selma called.

He turned. “Right. Ben.”

“Is there something I can do for you?”

“Uh . . . no. I just thought I heard something so I came down to have a look. Must have been you talking on the phone.”

“Are you feeling all right?” asked Selma. “You don’t look well.”

“Just fighting a little cold. Think I caught it from one of my little girls.”

CHAPTER 56

GRAND ST. BERNARD PASS, SWISS-ITALIAN BORDER

There were two routes for reaching the pass, Sam and Remi discovered, from Aosta on the Italian side of the border and from Martigny on the Swiss side, the path Napoleon and his Reserve Army had followed almost two hundred years earlier. They chose the shorter of the two, from Aosta, following the SS27 north through Entroubles and Saint Rhémy, winding their way ever higher into the mountains to the entrance to the Grand St. Bernard Tunnel.

A marvel of engineering, the tunnel cut straight through the mountain for nearly four miles, linking the Aosta and Martigny valleys and offering a weather- and avalanche-proof route beneath the pass above.

“Another time,” Sam said as they drove past and continued up the SS27. It would add almost an hour to their drive and with no way of knowing how long it would take to follow the riddle’s last line, they erred on the side of caution.

After another thirty minutes on the switchbacking road they passed through a narrow canyon and pulled into the lake basin. Split by the imaginary Swiss-Italian border, the lake was a rough oval of blue-green water surrounded by towering rock walls. On the eastern shore—the Swiss side—sat the hospice and monastery; on the western shore—the Italian side—three buildings: a hotel-bistro, staff quarters, and a cigar-shaped Carabinieri barracks and checkpoint. High above Sam and Remi the sun burned in a cloudless blue sky, glinting off the water and casting the peaks along the southern shoreline in shadow.

Sam pulled into a parking spot at the lake’s edge across from the hotel. They got out and stretched. There were four other cars nearby. Tourists strolled along the road, taking pictures of the lake and surrounding peaks.

Remi slipped on her sunglasses. “It’s stunning.”

“Think about it,” Sam said. “We’re standing in the exact spot where Napoleon marched when America was only a couple decades old. For all we know, he’d just found the Karyatids and he and Laurent were hatching their plan.”

“Or they were worrying about how to get out of these mountains alive in the middle of a blizzard.”

“Or that. Okay, let’s find ourselves a temple. It should be on top of the hill behind the hotel.”

“Excuse me, excuse me,” a voice called in Italian-accented English. They turned to see a slight man in a blue business suit trotting toward them from the hotel’s entrance.

“Yes?” Sam said.

“Pardon.” The man stepped around Sam and stopped at the bumper of their rental car. He looked at a piece of paper, then the license plate, then turned back to them. “Mr. and Mrs. Fargo?”

“Yes.”

“I have a message for you. A Selma is trying to reach you. She said it is urgent you call her. You may use the phone inside, if you wish.”

They followed him inside and found a house phone in the lobby. Sam punched in his credit card number and dialed Selma. She picked up on the first ring. “Trouble,” she said.

“We haven’t had a cell signal since Saint Rhémy. What is it?”

“Yesterday when I was talking to you on the phone one of Rube’s bodyguards—Ben—was walking around the workroom. I didn’t think much of it at first, but it started nagging me. I did a scan on all the Mac Pros. Someone had installed a hardware keylogger, then removed it.”

“In English, Selma.”

“It’s essentially a USB drive loaded with software that records keystrokes. You plug it in and leave it. However long it was installed it downloaded everything I typed. Every e-mail, every document. Do you think Bondaruk got to him?”

“Via Kholkov. Doesn’t matter right now. Is he there now?”

“No, and he’s late for his shift.”

“If he shows up, don’t let him in. Call the sheriff if you have to. When we hang up, call Rube and tell him what you told me. He’ll handle it.”

“What are you going to do?”

“Assume we’ve got company coming.”

They walked outside, grabbed their packs from the car, then circled to the back of the hotel and started up the slope. The grass was starting to green around the rock outcrops, and here and there they saw purple and yellow wildflowers poking up. When they reached the top of the hill, Sam pulled out his GPS unit and took a reading.

“You think they’re already here?” Remi said, scanning the parking area with her camera’s zoom lens.

“Maybe, but we can’t second-guess ourselves. There are hundreds of people here. Unless we want to leave and come back later, I vote we push on.”

Remi nodded.

Eyes fixed on the GPS screen, Sam walked south a hundred feet, then east for thirty, then stopped.

“We’re standing on top of it.”

Remi looked around. There was nothing. “You’re sure?”

“There,” Sam said, pointing beneath his feet. They knelt down. Faintly visible in the rock was a chiseled straight line, roughly eighteen inches long. Soon they could make out other ruts, some intersecting, others moving off in different directions.

“Must be what’s left of the foundation stones,” Remi said.

They walked to what they guessed would have been the center of the temple, then faced east. Sam took a bearing with the GPS, picked out a landmark on the other side of the lake, and they headed back down the hill. At the bottom they crossed the road they’d driven in on and followed a path along the shore, past a stone block bistro fronted by a wooden walkway, then onto a rock shelf that ran along the water to a sheer ledge. Here they dropped down and followed a trail around a small cove to another flat area littered with boulders and patchy grass. Above them the cliff shot up at a fifty-degree angle. In the shade of the peaks, the temperature had dropped ten degrees.

“End of the line,” Sam said. “Unless we’re supposed to climb.”

“Maybe we missed something back the way we came.”

“More likely two hundred years of erosion turned whatever ‘bowl’ was here into a saucer.”

“Or we’re overthinking it and they were talking about the lake itself.”

A gust of wind whipped Remi’s hair across her eyes and she brushed it away. To Sam’s right he heard a hollow whistling sound. He snapped his head around, eyes scanning.

“What’s wrong?” Remi asked.

Sam held a finger to his lips.

The sound came again, from a few feet away. Sam moved down the face and stopped before a granite slab. It was ten feet tall and four feet wide. Two-thirds of the way up was a diagonal crack filled with yellow-green lichen. Sam stood on his tiptoes and pressed his fingertips to the crack.

“There’s cool air blowing out,” he said. “There’s a void behind this. That top piece can’t weigh more than five hundred pounds. With the right leverage we could do it.”

From the packs he withdrew a pair of Petzl Cosmique ice axes and slipped them into his belt. Though unsure of what they’d find once they reached the pass, it had seemed unlikely the Karyatids were tucked away in a closet in the hospice. The most likely hiding place would be either in some high, hidden cranny or somewhere underground.